The sense of satisfaction that comes from covering greater distances in a faster time. The excitement of testing your limits. Trail running offers a unique enjoyment that is different from either hiking in the mountains or road running. That is why so many people get hooked on it, and for some, the challenge naturally leads to an interest in even tougher, longer races all over the globe.

However, races in mountainous areas, especially at high altitudes, come with their own challenges. Runners must keep moving despite dramatic temperature changes between day and night, strong winds along ridgelines, and sudden storms. This makes careful gear selection essential.

You need to keep your gear as lightweight as possible to minimize the burden over long distances, while also ensuring you are prepared for unexpected situations. Deciding what to bring and what to leave behind is key.

So, how should you choose your gear?

The best approach is to gain experience over time and gradually refine your choices. But of course, it is natural to feel uncertain, especially in the beginning.

To help guide you, we spoke with Tsutomu Iwasaki, a seasoned mountain runner and finisher of TJAR, one of Japan’s most renowned races. Let’s hear his insights on preparing for the challenges of trail running in the mountains.

Tsutomu Iwasaki is a long-distance trail runner and a finisher of TJAR.

Tsutomu Iwasaki is a 57-year-old trail runner. His first trail running race was the Mt. Fuji Hill Climb. Surprisingly, that race was also his very first time summiting Mt. Fuji.

Tsutomu Iwasaki (in the distance: Kangtega, 6,782m on the left, and Thamserku, 6,608m on the right)

A few years later, Iwasaki entered the Hasetsune Cup, intending it to be his first and last race. But he surprised himself by finishing 17th overall, a remarkable achievement that drew him deeper into the world of trail running.

He went on to participate in Japan’s premier long-distance mountain race, TJAR, multiple times and successfully completed the grueling course. His passion did not stop there. Iwasaki also completed the Ultra Gobi Race, a 400km challenge across the Gobi Desert, not once but twice.

Just last month, he returned from the Great Himal Race, a monumental event that traverses the Himalayas from west to east. The Great Himal Race covers a total distance of 1,700km, with a cumulative elevation gain of 90,000 meters, over a period of two months. It stands out as one of the most extreme long-distance races in the world.

And with a race of this scale, unexpected challenges are simply part of the journey.

We sat down with him to hear about the race, going over maps and other materials together.

A long-distance race where the unexpected is the norm

Q: Welcome back. It’s incredible that you made it through such an unimaginable race safely. I’m sure it must have been incredibly tough. Could you tell us more about it?

Iwasaki: Thank you. Yes, it was really tough. It felt like a double punch, with both the weather conditions and sanitation issues.

At the start of the race, the region was geographically high and extremely dry, with low temperatures. On top of that, there were lots of animals, such as yaks, cattle, horses, sheep, and goats. Their droppings were scattered everywhere. Because it was so dry, the dung would break down into fine particles, mix with the dust, and get kicked up into the air.

That led to respiratory problems. For me, it meant a persistent cough that would not go away. It wasn’t just me. Most of the runners, to varying degrees, struggled with respiratory issues.

The dry regions of the western Himalayas.

Q: The environment must have been completely different. We also heard that you had some health issues at one point, and we were quite concerned. But you managed to recover and return to the race, didn’t you? Everyone here was following your progress closely.

Iwasaki: That’s right. The immediate reason for my temporary withdrawal was severe food poisoning.

Late at night, I started having diarrhea and vomiting about 20 times in total, and I couldn’t move. Fortunately, the symptoms stopped by the evening, so I was able to rejoin the race the next day.

However, I had no appetite at all and could barely eat anything for two or three days. I was essentially running on empty, breaking down my own muscles and body to create energy. At that point, I realized that if I kept going, I would probably collapse completely.

I was determined to finish the race, and I really didn’t want to step away. After giving it a lot of thought, I made the difficult decision to pause and focus on recovery before rejoining the race.

One interesting thing about this race is that because it is such a long event, the rules allow runners to temporarily withdraw and then return to the course later. That is why I was able to get medical attention in Kathmandu after being transported by jeep and plane. I was then able to rejoin the race at Annapurna.

A photo taken on the third day after the onset of food poisoning, just after deciding to temporarily withdraw.

Q: Annapurna is known for its incredible scenery. How was it for you?

Iwasaki: That’s right! The weather was good, and I was able to enjoy some incredible views.

The plan was to have Annapurna as the main highlight in the first half, and Renjo La Pass in the second half.

I was especially looking forward to Renjo La because you can see Everest, Lhotse, Makalu, and Cho Oyu all at once from there. But unfortunately, it was completely fogged in, and I couldn’t see a thing.

I figured maybe it was a sign to come back again someday, so I took some photos in the thick fog anyway.

A breathtaking view of Annapurna.

Renjo La, where thick fog obscured the stunning views.

Q: Were there any other moments that left a strong impression on you?

Iwasaki: One of the most challenging parts was dealing with the schedule changes. In Japan, race organizers always announce the start and finish locations in advance, and the start times and checkpoints are clearly set. But in this race, the finish points, routes, and even start times often changed at the last minute.

There was one time when we were told the start would be at 7:00 a.m., so I prepared accordingly and arrived at the start line. But when I got there, I found out the start had been moved up to 6:30 a.m., and everyone had already left.

Another surprising moment was during a pre-race briefing when they mentioned that there might not be a lodge at that day’s finish point. And sure enough, when we arrived, there wasn’t one. Looking around, we noticed an arrow drawn on the ground with trekking poles, pointing us in the right direction.

We followed these arrows carefully at key points along the route, making sure not to miss them. But eventually, the markings disappeared completely, and we had no clear path to follow.

Later, I learned that there was a Japanese runner in the lead group. I used my satellite communication device, which was part of the mandatory gear, to message him and ask for the name of the village where we were supposed to stay.

However, when I checked the navigation app I had prepared before the trip, the village wasn’t listed. It only appeared on a local map app I had installed with the help of a Nepali runner during the race. Even then, there were multiple routes to the village, and I wasn’t sure which one was correct. Somehow, I managed to make it there.

That day, participants ended up scattered across three completely different locations.

Gear for Running into the Unknown

Q: You really had to make use of everything at your disposal to keep going. In such a long race with athletes from all over the world, I imagine you must have seen differences in culture and habits as well.

Similarly, I would expect that each runner’s choice of clothing reflected their own unique approach, which can be a key factor in performance. What kind of clothing did you wear for the race?

Iwasaki: This time, I based my layering system on what I had used for the Ultra Gobi, and it worked out well in terms of comfort.

The main difference between the Ultra Gobi and the Great Himalaya Trail was the altitude peak. In the Ultra Gobi, the altitude peaked just over 4,000 meters, while in the Great Himalaya Trail, it went as high as 5,755 meters.

The Ultra Gobi course is located at a much higher latitude, roughly equivalent to Southern Hokkaido in Japan (or Southern Oregon or Northern Italy in Europe). The race also took place in October. The Great Himalaya Trail, on the other hand, was held at a much lower latitude, similar to the area just north of the Okinawa Islands (or Northern Mexico or Northern Egypt), with the milder temperatures of May and June.

Still, because the Great Himalaya Trail went through much higher altitudes, I needed to be prepared for cold conditions down to minus 20 degrees Celsius. I figured that using a similar layering system to the Ultra Gobi would be sufficient.

The complete set of gear used for the race

1. Elemental Layer Warm Short Sleeve

2. Ramie Spin Air Zip Neck Short Sleeve

3. Merino Spin Light Zip Neck

4. Merino Spin Thermo Hoodie

5. Sky Racer Shorts

6. Everbreath Regn Pants

7. Polygon UL Pants

8. Elemental Layer Warm Tights

9. Polygon UL Jacket

10. Elemental Layer Warm Sleeves

11. Everbreath Regn Jacket

12. Skytrail Breath Cap

13. Elemental Layer Warm Balaclava

14. Merino Spin Balaclava

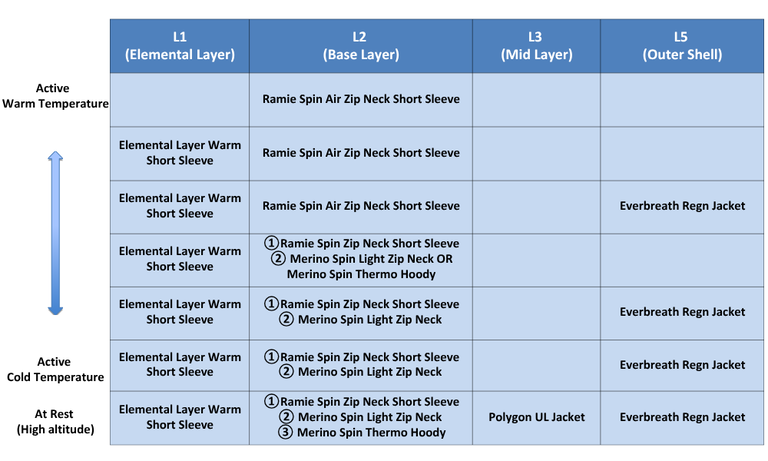

Q: Even so, temperatures can drop to minus 20 degrees, right? From what I can see, your overall layering system seems quite lightweight. How did you decide which pieces to use and when?

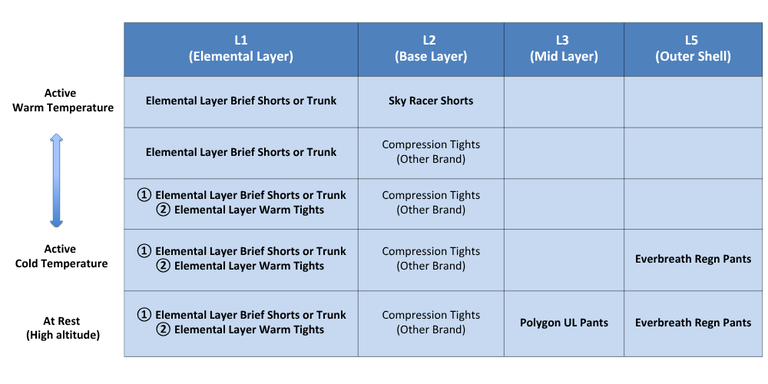

Iwasaki: My basic setup was the Elemental Layer Warm Short Sleeve with either the Elemental Layer Basic Briefs or Boxer Shorts, the Ramie Spin Air Zip Neck Short Sleeve, and either the Sky Racer Shorts or Recovery Tights.

For example, at the start of the day or in colder conditions, I would add the Elemental Layer Warm Sleeves, gloves, and the Skytrail Breath Cap. Once it warmed up or my body heated up, I would remove those accessories to adjust my temperature. This system worked for most conditions up to around 4,000 meters, as long as the weather wasn’t too bad.

Iwasaki explaining his race layering system.

When we went above 5,000 meters or when the weather turned bad, I would put on an outer layer for protection. In some cases, even during the day, the temperature could drop below minus 10 degrees Celsius. In those conditions, I would add a base layer over my Elemental Layer Warm Short Sleeve and also wear the Everbreath Regn for extra protection.

At high mountain passes, where my cheeks, ears, and face would start to hurt from the cold, I also used the Elemental Layer Warm Balaclava.

After arriving at a lodge, I wore the Polygon UL almost every day for warmth, whether while sleeping or during the time leading up to our early morning starts.

Layering System (Tops)

At the start of the day, when it felt cold, the Elemental Layer Warm Sleeves and gloves were added. At higher elevations, in windy or rainy conditions, the Elemental Layer Warm Balaclava and the Merino Spin Balaclava were used for extra protection.

Layering System (Bottoms)

At Rumbasamba, 5,159 meters. The layering system and Iwasaki’s appearance speak to the intensity of the race.

Q: Layering multiple base layers seems like your own unique approach. It really shows how important precise temperature control is. If you had to choose an MVP among your carefully selected gear, which one would it be?

Iwasaki: Definitely the Elemental Layer Warm and the Ramie Spin Air Zip Neck Short Sleeve.

The zip on the Ramie Spin Air makes it easy to adjust your temperature, which really expands the range of conditions it can handle. The Elemental Layer Warm, when paired with the sleeves, works as a long-sleeve, and together they can accommodate a wide range of temperatures. I wore it so much that the fabric on the shoulders started to thin from the abrasion of the pack, but it would still dry so fast after sweating or washing.

The Essential Item: Elemental Layer

Q: The Elemental Layer comes in Warm, Regular, and Cool. For running, most people tend to use the Elemental Layer Cool or Regular. But you chose to bring the Elemental Layer Warm. Why was that?

Iwasaki: Yes, I use the Elemental Layer Warm as my main layer, even in Japan.

Of course, if I have the option to leave gear behind at a checkpoint, I’ll switch layers as needed. But in a situation where I need to keep my pack as light and compact as possible, if I have to choose just one, I’ll always go with the Elemental Layer Warm Short Sleeve.

For cold weather, long sleeves are definitely better, but with some creativity, you can achieve the same level of protection using the Warm Short Sleeve.

The reason I choose the Elemental Layer Warm is that it offers the most warmth, and even when it gets wet from rain, it doesn’t feel clammy or cold.

Q: So, for a race like this, running for two months through high-altitude mountain terrain, you prioritized protection against the cold and wet, and that’s why you chose the Elemental Layer Warm, correct? Were there any moments during the race when you were particularly glad to be wearing the Elemental Layer?

Iwasaki: In the early part of the race, in April, the far western region was extremely dry, with dust blowing everywhere. After rejoining the race in May, through the central and eastern sections, there were actually a lot of rainy days. Thanks to the Elemental Layer, I was able to maintain body temperature and feel confident going into the race, despite the varying conditions.

I’ve had plenty of experience moving through ridgelines in the Japanese Alps during storms. Before I discovered the Elemental Layer, there was one time in bad weather at high altitude when I almost became hypothermic. But ever since I started using the Elemental Layer, I’ve been able to move safely even in those conditions without feeling at risk.

That track record is exactly why I felt so confident using it for this race.

Q: I see. You’ve faced so many challenging conditions, and it’s those experiences that brought you to the stage of the Great Himalaya Trail. For a seasoned runner like you, what does the Elemental Layer mean to you?

Iwasaki: For me, it’s an essential item. It’s something that protects my life whenever I’m in nature, especially at high altitudes, regardless of the season or location.

Finally reached the goal! At Kanchenjunga Base Camp, 5,143 meters, with a fellow Japanese participant (left) and the Nepali guide who supported me (right).

By pushing your limits, you begin to see views that were once hidden.

Q: Thank you so much! Could you share your thoughts on what’s next for you, and any advice you might have for those aspiring to take on ultra-distance races?

Iwasaki: As for my next goal, I’d like to try the Great Himalaya Trail again. I wasn’t fully prepared for the dryness, high altitude, low temperatures, and poor sanitation, so I want to rethink my approach and give it another go. There’s also the fact that I missed the view from Renjo La due to fog, which still feels like unfinished business for me. For reference, the next Great Himalaya Trail is scheduled for October to December 2027.

For anyone aiming to take on ultra-distance races, I encourage you to gain as much experience as you can, wherever you are now. There are so many great long trails across Japan and around the world, so I’d recommend starting during the snow-free season. Then, as you build your skills, try exploring different areas in different seasons.

I’d also love to see more people taking on challenges overseas. There are things you simply can’t experience in your home country, and I believe you’ll gain new perspectives and discoveries by stepping out into the world.

Tashilapcha, 5,755 meters. This was the highest point of the race, and technically the most challenging area, with crevasses, blue ice, and sections requiring ropework to pass.

How did you like the interview?

Iwasaki’s extraordinary stories are truly one-of-a-kind. We actually covered a lot more in our conversation, but we’ll save the rest for another time.

Of course, exactly copying someone else’s gear setup from head to toe isn’t always the best answer. But I hope Iwasaki’s insights serve as a valuable reference for you.

With carefully chosen gear that suits your needs, be ready for the unexpected, and take on the challenge of long-distance races safely.

Together with the race finisher’s certificate and Finetrack founder and president Yotaro Kanayama.

Tsutomu Iwasaki

Based in Osaka, Japan.

Iwasaki started trail running in 1993 after competing in the Mt. Fuji Ascent Race. Since then, he has raced through mountains across Japan and around the world, including New Zealand, Malaysia, China, and Nepal. He has participated in over 330 races to date.

In recent years, Iwasaki has established himself as an ultra-distance trail runner. He completed the Trans Japan Alps Race in 2016, finished the Ultra Gobi two years in a row (becoming the first Japanese finisher in 2017), and completed the Great Himalaya Trail Race in 2024.